Stanford researchers honored with 2025 Breakthrough prizes

The awards recognized early-career researchers in physics and mathematics as well as a massive project that includes many Stanford scientists and aims to understand the fundamental structure of the universe.

When the red carpet was rolled out for the Breakthrough Prize celebration, also known as the “Oscars of Science,” in early April in Los Angeles, several Stanford stars won big.

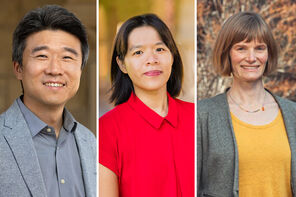

Jeongwan Haah, an associate professor of physics in the School of Humanities and Sciences, received the $100,000 New Horizons Physics Prize, which is given to promising early-career researchers who have already produced important work.

Si Ying Lee, a Szegö assistant professor in mathematics in H&S, won the Maryam Mirzakhani New Frontiers Prize, recognizing outstanding women mathematicians who have recently completed their doctoral degrees. The prize, which comes with $50,000, is named after the late Stanford mathematician Mirzakhani, who was the first woman to win the Fields Medal, considered to be like the Nobel prize for mathematics.

One of the foundation’s top prizes, the $3 million Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics, went to what just might be the biggest group project in the world: four experimental collaborations representing 13,508 researchers. These projects, known as ATLAS, CMS, ALICE, and LHCb, are taking place at the CERN Linear Hadron Collider.

The ATLAS experiment includes a large group of researchers from SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory as well as the Stanford lab led by Lauren Tompkins, associate professor of physics in H&S.

A new area of mathematical physics

As a graduate student in 2011, Haah made a discovery that surprised the physics world: finding a mathematical model of a 3-D quantum phase involving fractons, types of partial particles that can be stable in a locked pattern. This discovery, now called the Haah Code, opened up a new area of investigation that may one day lead to a type of quantum “hard drive,” a key component for realizing the super-capacity of quantum computers.

While the discovery was a big moment in the field, Haah is prouder of the rigorous mathematical work he did later to describe the code and explore its implications. The New Horizons Physics Prize recognizes his fundamental work that spans both math and physics.

“Mathematical physics can bring new phenomenology to the table,” Haah said. “Rather than just formulating a well-understood problem in mathematical language, you can find an opportunity and discover something new.”

Haah was also honored to receive the news of his award through a phone call from the theoretical physicist Alexei Kitaev, one of his heroes and winner of the Breakthrough Prize in Theoretical Physics in 2012.

Inspired by Mirzakhani’s legacy

Lee was also connected to one of her heroes through the Mirzakhani prize, which is intended to support promising women mathematicians.

“Winning this prize was both a validation of my research and a real honor since it is named in the honor of Maryam Mirzakhani,” she said. “Mirzakhani was a great inspiration to me and I'm sure to every woman mathematician. When she won the Fields Medal, it was a sign that women can do top-tier mathematics research as well.”

Lee received the prize for her work finding a new approach to a problem in the Langlands program, which mathematician Edward Frankel called a “grand unifying theory of mathematics.” Lee added to this effort to bridge disparate areas of the field by contributing to the theory of Shimura varieties, which are a special type of classifying spaces that can connect number theory and geometry.

“I want to acknowledge all the people who have helped me,” Lee said. She credited her collaborators, her mentor Richard Taylor at Stanford, and her doctoral adviser Mark Kisin at Harvard. Other mathematicians both at the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in Germany and at Stanford as well as her family have also supported her career.

“They have all been extremely valuable to my progress, and all this would not have been possible without their support,” she said.

The structure of the universe

The size of the project at the CERN Hadron Collider in Switzerland matches the ambition of its goal: to test the modern theory of particle physics. This includes measuring the properties of the Higgs boson particle. Discovered at CERN in 2012, its existence helps explain how any particles in the universe have mass.

“The prize is a recognition of the value of this large scientific collaboration; it really does take this many people all working together to study the smallest pieces of the universe,” said Tompkins, who has been working on projects related to the collider for 20 years.

The fundamental physics honorees donated their prize money to the CERN Society & Foundation to offer grants for doctoral students from member institutes to do research at the hadron collider.

Haah is also a member of Stanford’s Q-FARM initiative.

Media contact: Sara Zaske, School of Humanities and Sciences, szaske [at] stanford [dot] edu (szaske[at]stanford[dot]edu)