Geospatial technology to be used for analysis of Holocaust testimonies, travel writing

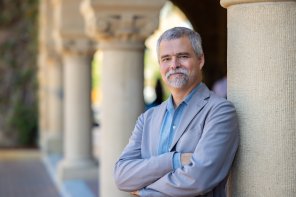

Stanford historian Zephyr Frank has been awarded nearly $500,000 to help direct a study of how software designed to precisely map complex geographic data can be used to analyze and represent ambiguous spatial information in large collections of text.

Geospatial technology has many familiar applications, from tracking nuclear submarines to mapping deforestation in the Amazon. Now, a Stanford historian and his colleagues are deploying it for a distinctly unusual purpose: analyzing travel writing and Holocaust survivor testimonies.

Zephyr Frank, a professor of history in the School of Humanities and Sciences and of environmental behavioral sciences in the Doerr School of Sustainability, has been awarded nearly $500,000 from the National Science Foundation to help direct a study of how software designed to precisely map complex geographic data also can be used to construct spatial representations based on imprecise and subjective descriptions of places.

The goal is to map or otherwise depict themes, patterns, and connections that only emerge when computational tools are applied to thousands of pages of text.

“We want to explore how geographic information systems and related digital tools can identify, analyze, and visualize ambiguous spatial information in narratives,” said Frank, the Gildred Professor in Latin American Studies and co-founder of the Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis at Stanford.

The project, a joint initiative with the U.K. Research and Innovation organization, unites research groups from Stanford, Lancaster University, the University of Leeds, and Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis. They will use natural language processing, qualitative spatial and temporal reasoning, advanced visual analytics and representation, and geographic information systems to depict three characteristics of place: location, the natural and human-made physical environment, and sense of place, which they define as “the accumulated events, actions, and memories attributed to a location.”

Building on their previous work funded by the UKRI’s Space and Narrative in the Digital Humanities network, the team will investigate written descriptions of the Lake District, in England, known for its moody and mountainous landscapes, and testimonies of Holocaust survivors, whose movements and encounters with new places occurred under stressful and disorienting conditions.

The researchers will analyze 1.5 million words of travel writing and tourist literature about the Lake District produced between 1622 and 1900 as well as relevant material from 18th- and 19th-century books in the British Library. Some of the travel writing is by famous poets, such as William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The team also will analyze roughly 1,300 Holocaust survivor testimonies provided by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

“The contrasts between these two corpora are obvious: One portrays leisure journeys where the aim is to describe the landscape and evoke an emotional response,” the researchers write in a project description. “The other describes forced journeys undertaken by traumatized participants, narrated decades later, describing some of the darkest events in modern history. One is written, the other spoken. Both, however, describe journeys in which the narrators reflect their experiences of geography in subjective, often imprecise, language.”

If you’re merely human, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to wade through all of that text and detect patterns, such as particular words, that pop up in connection with certain places. But a computer can do this in a few seconds or less.

Then, researchers can ask questions such as: How did motifs in travel writing about the Lake District change after the region was linked by rail to London? How was time and space distorted or compressed in the crucible of forced movement during the Holocaust as narrated in survivor testimonies?

This type of information can be shown with geospatial software, Frank said. For example, using GIS for base geography, the team plans to experiment with overlaying network graphs connecting terms and concepts attached to the landscape. “Concepts of place and related structures of feeling will be represented in layered visualizations,” he said.

The investigators aim to produce material that can be displayed or made available to the public through the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and the National Trust in the U.K.