On Writing and Identity: An Interview with Author and Professor Chang-rae Lee

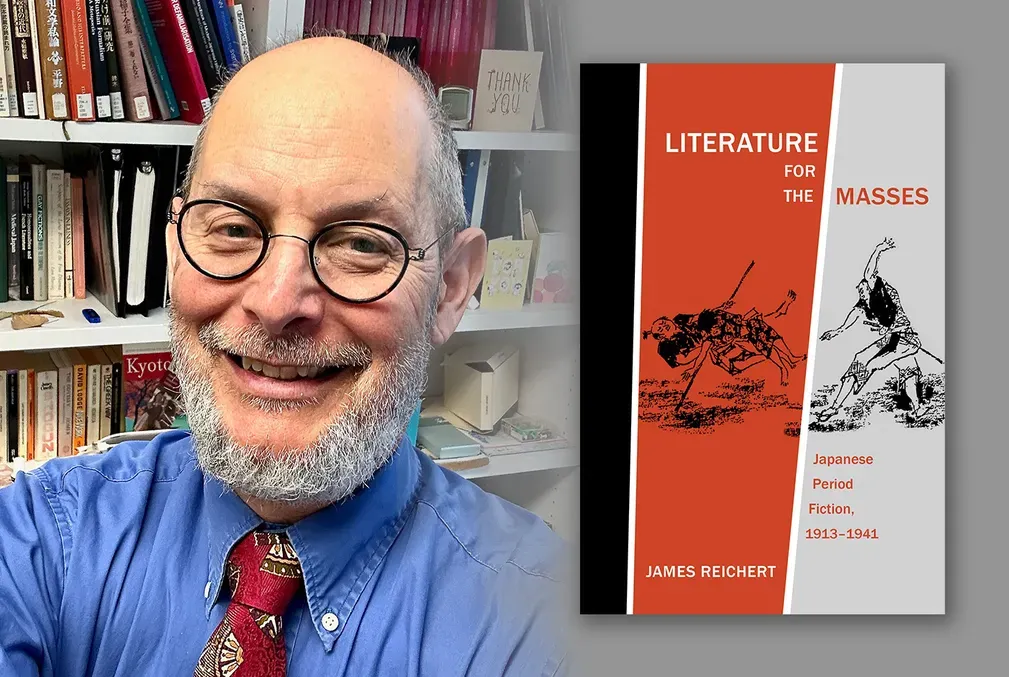

In the fall of 2016, acclaimed author Chang-rae Lee joined Stanford as the Ward W. and Priscilla B. Woods Professor in the English Department and Creative Writing Program. He was previously at Princeton University as a creative writing professor and director of their Program in Creative Writing.

Lee moved with his family from South Korea to the United States when he was three, and grew up in Westchester County, NY. His work explores themes of immigration, identity, alienation, and the intricacies of the Asian-American experience. He is the author of five novels: Native Speaker; A Gesture Life; Aloft; The Surrendered, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize; and On Such a Full Sea, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle and won the Heartland Fiction Prize. His novels have won numerous awards and citations, including the Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award, the American Book Award, and the Dayton Literary Peace Prize. He has also written stories and articles for The New Yorker, The New York Times, Granta, Conde Nast Traveler, Food & Wine, and many other publications.

What inspired you to study English and to become a writer? Where did that journey begin?

I remember the couch in my parent's old house where I just sat and read books all day when I was a child and was just amazed, aghast, shocked, titillated, and moved by it all. I read all kinds of stories, some literary and some not, in the early days. It was a way for me to feel alive.

That's really what reading is for me—feeling alive in a way that feels sustaining rather than sensational or momentary. Then, at some point, one thinks, "Wouldn't it be nice to be able to write something that gives another person that kind of feeling?"

As a teenager, I started writing mostly poetry. I have always been very attuned to language, maybe because I was an immigrant and English wasn't my first language. I was always very conscious of how people spoke and articulated their ideas and how everything sounded, tonally and rhythmically. So I think it was natural for me to write poetry first.

Later on, I started writing stories and it just went from there. This would not have happened without a lot of encouragement from teachers. Given my family background, I was not raised to become an artist or a writer. That was not part of my parents’ plan, or even mine, for a long time.

How did growing up as an immigrant influence your work?

I've always been compelled by the notions of context and individuality. This interest has been expressed in different ways across my books, but I think I've been consistently fascinated the question of persons who find themselves in a context that either fits too well or doesn't fit at all, by persons who feel they exist simultaneously inside and outside of a cultural or political space. It’s no surprise that as an immigrant I've always been extra conscious of this interplay.

What is the role of research in your writing?

I'm doing research all the time. Yes, I’ve done plenty of the traditional research that one can imagine, particularly for my historically based novels. But there's much "research" that can be done sitting on a bus and reading a strange book and having dinner with a loved one and watching the news. The key is to be extra-conscious of these everyday experiences, so that each moment or observation might be revealed as potentially textured and rich. I, for one, have gotten into the practice of carrying a mental notebook throughout the day.

What motivates you to sit down at your desk every day to write?

Two things, I think. One is the dread of silence. I'm not a very talkative person or someone who is naturally performative, so what I mean by the dread of silence is the fear of not giving expression to my internal voice, the one that keeps asking questions about this life.

The other motivation is the love of the pure freedom I have when I write. It's the freest thing you can ever do, an act without boundaries and obligations.

The first class you taught at Stanford was an introductory fiction workshop for undergrads. What excites or inspires you about teaching students?

Part of the reason I enjoy teaching undergrads is because they don't come to the class with a lot of preconceptions about writing—they’re fresh and open to all kinds of ideas, story forms, voices, which is great. It’s really exciting to work with them because it compels me to articulate certain ideas with clarity and in a fashion that might best aid them when they think about their own work. And it reminds me, too, of the simple and inexhaustible joy of reading. I love that my students at Stanford, whether they are aspiring writers or mechanical engineers or computer scientists, have a creative urge that they just can’t deny. Working with them is definitely revitalizing.

Part of the reason I enjoy teaching undergrads is because they don't come to the class with a lot of preconceptions about writing—they’re fresh and open to all kinds of ideas, story forms, voices, which is great.

Do you have a particular approach to teaching creative writing?

I focus on close reading and ask them to try to almost memorize the assigned texts. It's hard to do but incredibly useful. In class, we try to move through a short story sentence by sentence, considering what the writer is building in terms of language, character, context, emotion, meaning.

What do you hope students learn from doing that kind of close reading?

I don't think they're actually that practiced in paying such sustained and close attention. It would be my guess that literature to some of them is, unfortunately, perhaps just another kind of information for the sake of information, for the sake of conveying some set of facts. As noted, I ask them to slow down and atomically parse sentences and paragraphs. My hope is that they begin to realize there's another kind of construction going on beyond the construction of reality, something more mysterious. In the end, I think that's what I hope they get – that there's beauty in all of this. That beauty is various, unlikely, but it’s there.

Can you speak to the value of studying literature and the humanities more broadly?

When we pursue such study, we're attuned to a level of experience that allows us later on to make connections and become open to possibilities that I don't think we'd be able to do otherwise. The humanities de-ossifies us, and broadens our natures. It might seem to some that this kind of study doesn't have a purpose or verifiable outcome in the ‘real’ world, but, in fact, it's the ultimate purpose. It’s the ultimate outcome, which leads to all others of worth, and I believe the world needs people who can make those connections.

Are there stories that you think need to be told that aren't or stories that you think we need to hear today?

I recently read a new book by Mohsin Hamid, Exit West. It's a story about migrants and migrancy and the philosophical and emotional contours of that existence. It’s a book that is investigating a major question of our time, and the kind of story I’m interested in. Migrancy and immigrancy of course are related; they're different facets of a single experience.

I think we need stories that bring up questions such as, “What is a homeland?” “Who belongs where?” “How do we think of our belonging in a world that is increasingly globalized?” And of course, “How do we get along?”

These are questions that I’m enthused about, because this is our present global reality.

Finally, several of your essays center around food—what is your favorite meal to cook, or a go-to dish in your household?

My wife and I have this conversation a lot because she comes from an Italian-American family but she loves Korean food, too. And I love Italian and Italian-American cuisine.

We go back and forth between two very basic dishes. The first is linguine with clams. It's so simple. It's perfect in many ways—the clam is a creature that contains the seas, and with the pasta and garlic, it's always so elemental and wonderful. The second is a Korean stew with pork belly and kimchi.

They're both very earthy in their own ways. If I had to make last meals for my family, I think those would be the two. The reason why I love food is because food is life. It's not just about nourishment. Each dish contains the world and everything that the world is. It's an affirmation of existence.