Writers drew attention to how they listened to ‘common people’ in 19th-century Russian Empire, according to Stanford scholar

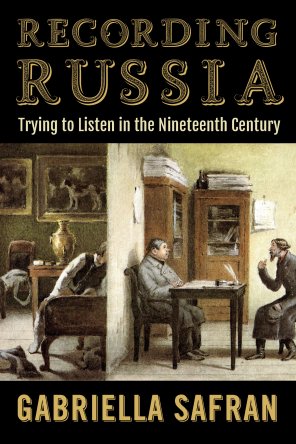

In a Q&A about her new book, Gabriella Safran discusses how new media technology and the notion of listening attentively shaped writers’ approaches to conveying the language and folklore of people in the Russian Empire in the 1800s.

Gabriella Safran, professor of Slavic languages and literatures in the School of Humanities and Sciences, was the editor of her high school newspaper in Boulder, Colorado. As a teenage journalist, she learned to appreciate the art of listening and recording.

“I still think of myself as a journalist,” she said in a recent interview about her new book, Recording Russia: Trying to Listen in the Nineteenth Century (2022, Cornell University Press). “It was a very formative experience for me. If you don’t have people listening, then you don’t get access to different points of view. You don’t get any kind of comparative perspective on anything. But listening is hard to do, right?”

Trying to do it well is what animates the subjects of her book: 19th-century writers, including Fyodor Dostoevsky and Ivan Turgenev, and visitors to the Russian Empire who sought to represent the perspectives of the “common people,” such as serfs and members of the working class, by listening to and documenting their voices.

Although the notion of “penitent noblemen” who struggle to communicate the “voice of the people” is a trope of Russian intellectual history, Safran asserts that political sympathy was only part of what motivated these writers to listen across social lines. They were also compelled by advances in media technology—the advent of telegraphy and the growing abundance and decreasing cost of paper—as well as the desire to compete with other members of what Safran calls “a global mid-nineteenth-century media generation” to display their mastery of listening and recording techniques.

“When they tell stories about listening and recording by themselves or their fictional stand-ins, these writers draw attention to sound and its transmission and to paper and its uses, and they tend to compare one person’s successful listening to another’s less successful listening (though often these rival listeners are two facets of a single person),” Safran writes. “In these scenes, the technical aspects of listening and recording, their political and ethical significance, and their practical and aesthetic import are interconnected.”

During the interview, Safran, who is also the Eva Chernov Lokey Professor in Jewish Studies and co-senior associate dean for the humanities and arts, discussed what listening and recording meant to these 19th-century writers and how shifts in media technology today echo what they were experiencing then.

Question: What sparked your interest in this subject?

Safran: Before I wrote this book, I wrote a biography of a Russian and Yiddish writer named S. An-sky, who was also an ethnographer. In reading memoirs about him, I noticed that his friends and acquaintances constantly talked about what a good listener he was—particularly, how good he was at listening to the common people, the narod. It was just fascinating to me that they were so attentive to that, and I wanted to figure out where that attentiveness came from. I learned that from about the 1840s, writers in the Russian Empire and writers who traveled there often drew attention to the idea that listening across social lines is something you can do well or badly. If you do it well, it’s a beautiful performance that should be appreciated. They also approached this practice competitively. The chapters in my book are framed as listening contests—between two people or, in some cases, between two sides of the same person. These 19th-century writers were eager to show how they had mastered modern techniques and technologies for listening and recording.

Question: To what degree was their listening performative as opposed to sincere?

Safran: It was both. They were sincere in their efforts to try to capture the authentic voices of peasants and other people. But they were also attuned to the performative aspect of listening; they wanted to show their readers that they were doing it right—that they were experts. They had ambivalent feelings about what they were doing, too. They knew how privileged they were; they were aware of the socioeconomic chasm that separated themselves from the people whose conversations they were recording. They were asking themselves, “Do I have the right to do this? Am I even doing it accurately? What is ‘accurately’?”

Question: Do themes you explore in your book have resonance today?

Safran: Definitely. We're living in a moment when we are really interested in questions of representation. You see these questions raised a lot in art and in social media. When, if ever, do people have the right to speak on behalf of other people? These are the same questions that students in my folklore and literature course ask themselves. My students are very concerned about questions of the ethics and the logistics of listening across social lines. They're very interested in where those lines fall. Do you have a right to speak for your own relatives? Do you have a right to speak for your co-ethnics or people of your generation? If one of my students interviews his grandmother but doesn’t speak her language perfectly, he may ask himself whether he really grasps the stories his grandmother is relating. How do cultural, generational, and language gaps affect what is being heard and documented?

I also think that the issues of media technology I raise in my book resonate today, especially for us at Stanford and in Silicon Valley. We are at the epicenter of shifts in media technology that are changing the way the voice is heard, audibly or in writing, and recorded. These shifts are raising questions around reliability, authenticity, and truthfulness. The 19th century, with the development of telegraphy, phonography, and stenography, as well as mechanized paper production, is a really interesting analog to changes that are happening now. It shows us that some of the emotions that we're experiencing as new, like the feeling that comes with being able to record and post a video with our cell phones or instantly transcribe speech, have in fact happened before. Maybe we can understand something about ourselves by thinking about how people in the past asked similar kinds of questions under somewhat similar circumstances.

Question: You devote an entire chapter to papermaking, and paper is referred to a lot in other parts of your book. What was it about this medium that was so significant in the 1800s?

Safran: When you look carefully at a lot of 19th-century prose and poetry, you see many references to paper, and you grasp that writers lived in a world in which paper mattered. They cared about their access to paper. They cared about the quality of the paper that they wrote on. They cared about its cost. In the early 19th century, paper in Russia is still made by hand. This is difficult, painful labor—and not healthy for you. It’s often carried out by serfs. But in the mid-1800s, mechanized papermaking comes to Russia, and paper gets cheaper and cheaper and more abundant. For these writers, I think it’s a little bit like the revelation that comes today from realizing you can press a button on Zoom and get a transcript of your entire conversation.

Before, paper was made by hand, and it was really expensive. And no one would try to record every single word someone said—or, at least, that would be unusual. But with mechanically made paper, it's like this new world of verbatim recording that's ushered in. The arrival of that world produces a sense of excitement and also anxiety. So you see writers describing scenes where there is too much paper; people are drowning in it, weighed down by piles of heavy documents they have to process somehow.

Question: The fugitive quality of spoken language, which these writers were trying to capture, is implied in the book’s epigraph, an entry from a Russian-language dictionary produced by the lexicographer Vladimir Dahl: “A word is like a sparrow—it flies away and you can’t catch it.” Dahl refers to his dictionary entries as nests; a character in a story travels the countryside hunting birds and chatting with locals. What's with the avian references and metaphors in the work of these writers?

Safran: I was really fascinated by all the references to birds—the ways that people relate birds to words and words to birds—in the texts I was investigating. The writers use metaphors that make it seem like recording a spoken word is like capturing a bird. And they collect a lot of slang relating to birds or that uses bird words to describe humans in some way. Of course, comparing words to birds is nothing new. It’s a metaphor that goes back at least to classical times— Homer talked about the “winged word.” As far as the saying Dahl includes in his dictionary, it’s an effective metaphor about speaking cautiously, and at the same time it indicates how both birds and words flit away, eluding our grasp.