Women’s agency expressed through dance in Hindi cinema

By highlighting experimentation, collaboration, training, and mastery in the careers of Hindi cinema’s dancing women, Stanford art history professor Usha Iyer produces a new narrative about female labor in cinema.

The role of women’s dance in Hindi cinema has often been examined in terms of how dancing bodies further the story of a film or communicate something about the personality of a character or the relationship between characters.

Now, Stanford scholar Usha Iyer, assistant professor of art and art history in the School of Humanities and Sciences, argues that the dances performed by women in Hindi cinema actually signify much more. They are reflections not only of cultural history and changing cultural norms but also of the trans-regional cross currents that impacted South Asia.

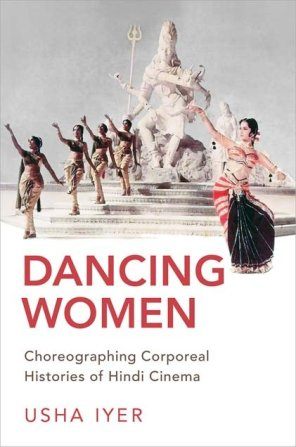

In her new book, Dancing Women: Choreographing Corporeal Histories of Hindi Cinema (Oxford University Press, 2020), Iyer examines not only the role of the dancer but also the special community of choreographers, backup dancers, and filmmakers who collectively created spectacular musical numbers.

“Shifting attention away from the ideological work performed by the song-and-dance sequence, which has dominated the study of Hollywood musicals and popular Indian cinema, to studying the industrial practices, training, rehearsal, and personnel required for these attractions produces a different history,” Iyer writes.

Many studies of women in cinema – both in the U.S. and around the world – have presented female performers as objects of the male gaze and victims of film industries. Iyer complicates this discourse by centering her analysis on female dancing and corporeality, and reveals a more complex picture of these “dancing women” than has been previously understood. She focuses on questions of labor and virtuosity around dance performance to construct a corporeal history that allows for a better understanding not only of cinema, but also of modernity more broadly.

In her scholarly work, Iyer shifts the focus from the spectacle of the idealized female form to the actual bodies doing the dancing and the tremendous training and effort required. “Then we don't just read women's bodies on screen as respectable or not respectable, as the evil vamp versus the virtuous heroine. Instead, we actually begin to look at their flesh, their bones, their skin.”

Most of the women Iyer references trained for years in dance, spending hours a day rehearsing, and these women remember their work with great pride. “They took care of entire families with the salary they earned from doing this work,” she said.

For the women who became stars, being a film dancer allowed for physical and social mobility, often allowing them some movement beyond patriarchal boundaries. “These women were not conventional wives, girlfriends, mothers,” Iyer said. “A lot of dancing women would put off marriage and childbirth to continue their careers.”

Impact on industry

Female dancers were not just a featured part of Hindi cinema, they shaped it. A dancer-actress could exercise great influence on the film, determining the choice of music composers and performers. Their dancing bodies mobilized cinematic technologies, including music, camera movement, editing patterns, and the early adoption of expensive color film for song-and-dance sequences.

For instance, Iyer demonstrates how the South Indian dancer-actress, Vyjayanthimala, transformed aspects of the Hindi film industry by introducing a new movement vocabulary as well as new choreographers, forcing a melding of north and south. “The southern dances required costumes, sets and props to change,” she said. “Through these South Indian dancing women, the films often had to tell stories that brought the country together. The same was true in many Hollywood musicals that would include a song set in the countryside even if the rest of the film took place in New York, so as to gesture at uniting America.”

For Iyer, film dance, which was typically considered inferior to “classical” dance, is in fact exciting to study precisely because it is marked by heterogeneity and creativity, with film performers drawing on dance forms from the Middle East, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Europe.

“Film dance was considered a corrupt mixture of classical, folk and western forms, not Indian enough,” Iyer said. “But I’m arguing it is a profoundly creative hybrid. I’m arguing that film dance is the modern dance form of India. If we move away from this binary of high and low art, we really discover very interesting things about our cultures.”

And for many lovers of Hindi film, the dance numbers are not simply fillers in between important plot points, but rather the grounding spectacles that connect their own bodies in deep ways to the attractions of cinema.

“We assume that what we remember in films is the plot,” Iyer said. “But all popular Indian films, including horror, are punctuated by song and dance sequences. People will return to watch a movie multiple times because of the spectacle of the song and dance number, because of the lived experience of toes tapping, fingers snapping.”