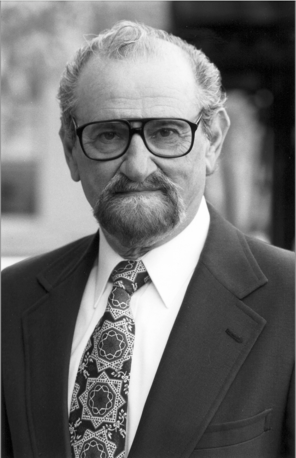

Stanford sociology professor Joseph Berger has died

A former chair of the Department of Sociology, Berger’s theoretical and experimental research explored how biases can shape social inequalities.

Joseph Berger, professor of sociology emeritus in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences (H&S) and former chair of his department, died Dec. 24. He was 99.

Berger is known for his pioneering research on status process, a theory and field that describes how people draw conclusions about others based on their memberships in socially advantaged or socially disadvantaged groups. Berger’s research led him to co-create the theory of expectation states, which relates to how people assign others to certain hierarchies based on social information like race and gender. This influential work helped researchers, psychologists, and others who interact with social information develop interventions to overcome these biases.

His contributions to the Stanford and global research community include establishing a theoretical and experimental research program at Stanford by using a lab to test and develop hypotheses in sociology—a novel approach to sociology at the time, but now a staple of the field.

“Joe Berger’s seminal ideas about status and expectations in interpersonal relations showed us how everyday encounters in places like the workplace, schools, or health organizations are systematically biased by things like gender, race, and class background,” said Cecilia Ridgeway, the Lucie Stern Professor of Social Sciences, Emerita, in the Department of Sociology in H&S. “Joe would argue fiercely with you over his ideas and yours but always with great intellectual honesty so that the argument opened up new understandings.”

Practicing 'Stanford sociology'

Berger joined Stanford in 1959 and immediately began establishing his research program, which was often called “Stanford sociology,” according to his 2014 interview with the American Sociological Association. This approach includes developing an explanatory theory for complex events and situations and then testing the theory, often in a laboratory.

As Berger noted in that same interview, his approach was an exception at the start of his career and was the rule by the time he retired in 1994. For example, as Murray Webster, Jr., a graduate student of Berger’s who earned his doctorate from Stanford in 1968, wrote in the ASA’s publication, Footnotes, Berger’s graduate seminar in theory construction, which he introduced upon arrival at Stanford, had been rejected by his previous university, Dartmouth, as too “radical.”

His contributions to the Stanford community include serving as chair of the Department of Sociology from 1976 to 1983 and from 1985 to 1989. He was also a senior research fellow at the Hoover Institution from 1986 to 1991; for two years prior, and the rest of his life after, he was a Hoover senior fellow (by courtesy).

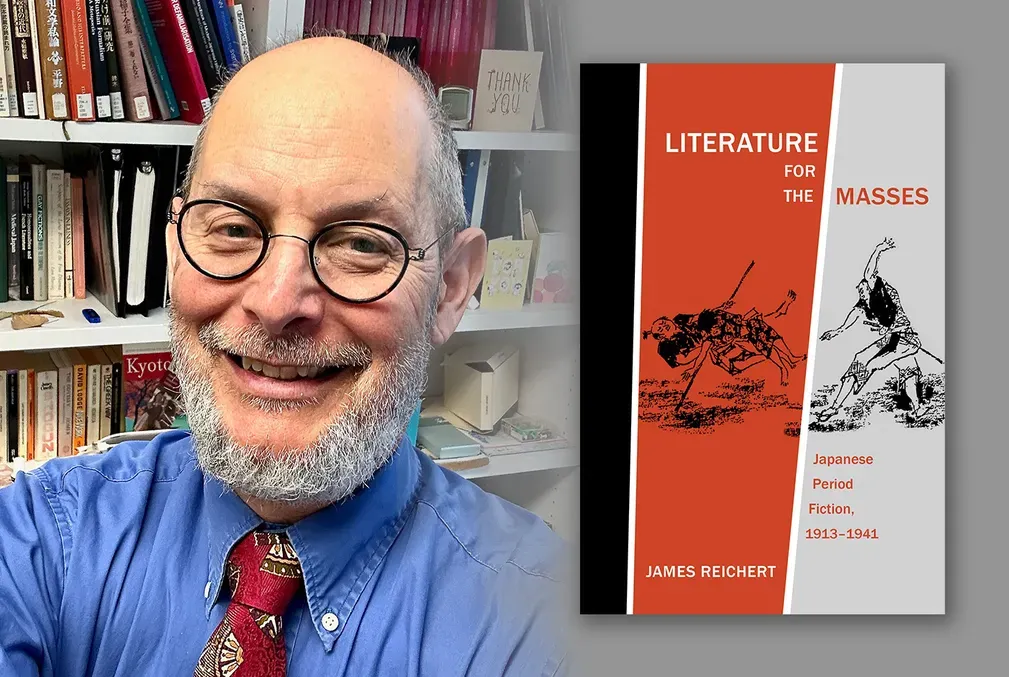

Berger wrote or co-authored more than 70 articles. He co-wrote three books: Types of Formalization in Small Group Research (Houghton Mifflin, 1962); Status Characteristics and Social Interaction: An Expectation States Approach (Elsevier Scientific, 1977); and Status, Power and Legitimacy: Strategies and Theories (Transactions Publishers, 1998). He also edited seven volumes including New Directions in Contemporary Sociological Theory (Rowman and Littlefield, 2002), which he co-edited with Morris “Buzz” Zelditch, Stanford professor of sociology.

In 1991, he received the Cooley-Mead Award from the Social Psychology Section of the ASA, in recognition of his long-term contributions. In 2007, he received the ASA’s W.E.B. Du Bois Career of Distinguished Scholarship Award for his contributions to the field of sociology.

“Joe Berger and the other young sociologists who arrived at Stanford from 1959 to 1961 saw themselves as revolutionaries, and, in many ways, they were,” said Webster, professor of sociology, emeritus, at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte.

“Berger and his colleagues at Stanford developed alternatives to impressionistic essays and untestable perspectives that had dominated sociology,” said Webster. “Their work promoting explicit, predictive theories and precise empirical testing methods influenced generations of Stanford graduate students. It is evident today in journal articles and papers and in growing understanding of social structures and social interaction.”

Webster described Berger’s generosity with his time and ideas in an essay he wrote for the Social Psychology Section in 2014.

“It is impossible to know how many hours Joe has given this way, discussing others’ ideas and making them better, or how many ideas he has given to someone who he thinks can develop those ideas,” Webster said. “To Joe this is part of the collective effort to develop abstract, rigorous, and testable theories in sociology.”

A lifelong sensitivity

Berger was born April 3, 1924, in Brooklyn to Jewish Polish immigrants. He described his father as a lifelong Marxist in the ASA’s 2014 interview. This upbringing made him, in his words, “extremely sensitive to the differences between socially advantaged and socially disadvantaged groups in society”—a sensitivity that defined his life’s work.

At age 18, Berger voluntarily enlisted in the Army during World War II and received a direct commission to officer, Second Lieutenant. He earned the Bronze Star and the Army Commendation Award for his work in military intelligence and information control. These experiences prompted him to move away from his father’s Marxism toward sociology as a way of understanding the class differences he had observed. In the ASA’s 2014 interview, he referred to his work as a “calling.”

He earned master’s and doctoral degrees in sociology at Harvard, where his closest mentors were the social theorist Talcott Parsons and Robert Freed Bales, a pioneer in the behavioral study of interaction in groups.

According to his colleagues and family, Berger was a lifelong student who could speak with deep knowledge, strong opinions, and great passion about astronomy and cosmology, classical music, World War II, world politics, and the founding fathers of the U.S.

Still publishing into his late 90s, Berger remained galvanized by his work. “Let me stress that there also are important problems that lie ahead in the study of group processes,” he said in the ASA’s 2014 interview. “And while it has been an expanding area of research over the past 25-30 years, I would argue that group processes is a research area that—fortunately—is still ‘in progress.’”

He is preceded in death by his wife, Margaret Alice Smith, who died in 2022. He is survived by his three children, Adam and Rachel (from a previous marriage to Shirley Fuchs) and Gideon, as well as four grandchildren.