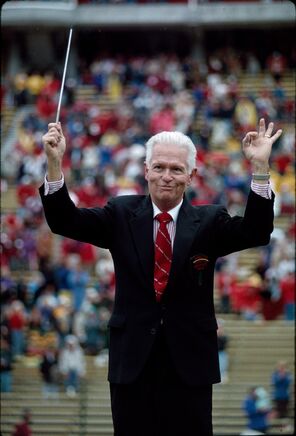

Stanford music professor Arthur P. Barnes dies at 93

Renowned for his talent as a conductor, musician, musical arranger, teacher, and mentor, Barnes helped transform the way music was played at Stanford and made significant contributions to the music community in the Bay Area and beyond.

Arthur P. Barnes, professor of music emeritus in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences and a musician whose skills as a performer, conductor, musical arranger, teacher, and mentor helped transform the way band music was played, died Feb. 5. He was 93.

Barnes came to Stanford in 1963 to complete a one-year doctorate in orchestral conducting. His skills were impressive and apparent enough that he was asked to conduct Stanford’s chamber orchestra, Wind Symphony, and the Incomparable Leland Stanford Junior University Marching Band that same year. He joined the music faculty in 1965 and began conducting Stanford’s Jazz Orchestra as well. He taught music theory, ear training, orchestration, and score reading at Stanford until his retirement in 1997.

Barnes’ talents as a musical arranger gave the Band its pop repertoire beginning in the early 1960s, and his musical know-how and warm, light touch as a leader fostered creativity and commitment among players for three decades. Under Barnes’s leadership, the LSJUMB performed in two Rose Bowls and for Queen Elizabeth II.

Barnes was “one of the finest musicians I’ve ever known,” said Fredrick J. Berry, who led the Jazz Orchestra after Barnes.

Berry, an accomplished trumpeter who has played with jazz legends including Count Basie, was Barnes’ student at Southern Illinois University and followed him to Stanford.

“People didn’t always realize what a great musician he was,” Berry said. “He was an incredible classical conductor, and he had the finest ear. Art made me more who I am as a teacher and a musician than anyone else.”

From Sousa to the Stones

In his first year leading the LSJUMB, Barnes earned it national acclaim. The assassination of President John F. Kennedy had caused a postponement of the 1963 Big Game, and the mood was somber as the teams prepared to take the field. Barnes led with his new arrangement of the “Star-Spangled Banner,” in which a single trumpeter plays the first half of the anthem. The sound of the lone trumpet reverberated in the stadium.

“I've never heard such a loud silence,” Barnes later recalled in a 2012 Stanford oral history. “All the sports writers said they had lumps in their throats. It was the defining moment of my early years.”

Leaning on Barnes’ skill for arranging, the Stanford Band shifted in the countercultural 1960s from a repertoire filled with Sousa marches to one fueled by the Rolling Stones, abandoning military-style formations in favor of the scatter style, in which players dart between static formations that often rely on humor. Stanford was among the first scatter style bands and helped pave the way for other university bands to adopt the style.

Barnes was quick to reject rock songs with little potential for brass and woodwinds and would press for changes if he thought scripts were out of line, but he rarely vetoed content.

“The ability in the ’60s and especially the ’70s to hear a tune on the radio, write it down, and arrange it was a tremendously special gift that Art had,” said Russel Gavin, who holds the Dr. Arthur P. Barnes Director of Band position endowed in Barnes’ honor. “I think the students immediately realized this guy was a real value-add. It helped that he was a cool, quirky guy himself. He was not a stick in the mud.”

Among the roughly 300 songs Barnes arranged, one stands out. In 1972, a little-known rock tune caught the ear of drum major Geordie Lawry, and Barnes charted it out for band. “All Right Now” has since become Stanford’s de facto fight song.

When Barnes announced he would retire from Stanford in 1997, six Stanford alumni then in the U.S. Senate presented a proclamation praising Barnes for his commitment to music education and his acclaimed arrangement of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

“Art gave the Band the love that it needed, both in terms of supporting the students in the group and advocating for the group around the university,” Gavin said.

A life in music

Barnes was born March 26, 1930, in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, the youngest of three boys. His father, who worked at General Electric, was a baritone vocalist; his mother was a pianist. Barnes excelled in his piano lessons early on. He soon picked up trombone and baritone horn, which he played in the Cleveland Heights High School Band. Barnes and his future wife, French hornist Helene, met in that band.

Barnes began his undergraduate education at Swarthmore College but soon transferred to Wichita State University, where Helene was. After graduating with a degree in music education, he married Helene, and both played in the Fort Wayne Symphony, with Barnes now on the bassoon.

As a multitalented musician with perfect pitch, Barnes saw his music career advance quickly. After earning a master’s degree in theory and composition from Wichita State University (1953), he served on the music faculty at Southern Illinois University (1953-1959). In 1959, he joined the music faculty at Fresno State, where he taught piano, trombone, and tuba and directed the band and the wind symphony. He also played in the Fresno Symphony, where Helene played, too. In 1963, Barnes moved with his family to Palo Alto.

As a music educator at Stanford, Barnes was known for providing his students with the inspiration and support they needed to perform their best.

“As I struggled with the challenges of being a Stanford undergraduate, it was Dr. Barnes who treated me as a junior colleague,” said former student Neil Grunberg, who earned his undergraduate degree in 1975. “He expected so much of me and demanded it of me. He encouraged and allowed me to create with him. He was a true mentor and phenomenal role model.”

In addition to his contributions to Stanford, he served as the music director and conductor of the Livermore-Amador Symphony from 1964 to 2014. During that time, several members of his family performed with the orchestra—his wife and son on French horn, one daughter on violin, another on bassoon, and a granddaughter on cello.

“Art had a degree of competence and excellence that made me want to be that good, too,” Berry recalled. “Everything he did was always excellent; there was nothing he did that was not.”

Arthur P. Barnes was preceded in death by his wife, Helene, in 2022. He is survived by his son, Jeffrey; daughters Jennifer Wolfeld and Holly Barnes; and five grandchildren. A memorial service will be held at Stanford Memorial Church on May 23 at 4:30 p.m. This service is open to the public.