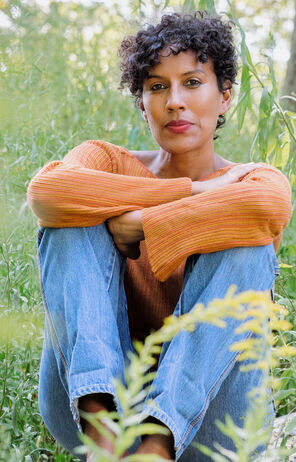

For poet Aracelis Girmay, poetry is a way of thinking through complexity

Writing and reading poetry offer, for the new faculty member, a chance to reflect on what our shared humanity means in a disconnected world.

What does it mean—what does it feel like—to live a human life in an age of high-tech global capitalism, rising authoritarianism, and planetary unrest?

For Aracelis Girmay, a poet who joined the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences as a professor in the English Department and member of the Creative Writing Program in September 2023, poetry offers one way to work through these questions. Girmay maintains that poetry doesn’t just describe human experience but rather crystallizes it.

“We are all carrying pieces of what it means to be,” she said. “You can touch those pieces against each other or not, but when you do, all kinds of things happen. Whatever it is you have to offer, when you offer it, you have to believe it can be met by another in some way.”

Girmay’s engagement with writing is both deep and broad. She has published three books of poetry, including most recently the black maria (BOA, 2016), which was mentioned when she was named a finalist for the prestigious Neustadt International Prize for Literature in 2018. Kingdom Animalia (BOA, 2011) was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Girmay has written the text for three children’s books and recently put out a chapbook of poetry, and was a flower, in collaboration with the book artist Valentina Améstica. She has also edited How to Carry Water: Selected Poems of Lucille Clifton (BOA, 2020) and So We Can Know: Writers of Color on Pregnancy, Loss, Abortion, and Birth (Haymarket Books, 2023). With an MFA from New York University, Girmay came to Stanford from the Pratt Institute in New York, where she was a writer in residence.

Girmay’s work helps make her case for the palpable humanity in poetry. Readers experience moments of shared feeling that collapse the distance between writer and reader. For example, in “Abuelo, Mi Muerto” (Kingdom Animalia), the poet grieves her grandfather as she meanders through the city where he lived:

your way back home from the train, & trees

you passed a thousand times

like a child below the grey gaze of its mothers.

How could I be lost here

in your jackal-mouthed, murderous

streets who swallowed your children, Abuelo,

while the church bells marked the parish & hour?

Girmay captures the feeling of having someone who is lost feel suddenly close in time in a particular place. The description shuns pretense even as it teems with lyricism in the service of political remembering.

Telling and hearing stories

Girmay was born in Southern California to an Eritrean father and an African American and Puerto Rican mother from Chicago. Girmay loved to listen to them both tell their stories. Through language, they conjured memory and belonging.

“I just loved the turns of phrase and language,” she said. “There was something about not just the story and what the story communicated, but also what the sound itself signaled about ancestry, the relationships to a ‘back home.’”

Girmay recalls committing to poetry as an undergraduate at Connecticut College, where she majored in documentary studies. Working on an oral history of Black Nicaraguan women community leaders with a local human rights group, Girmay’s job was to transcribe the interviews.

“I realized in that transcription work, which was so difficult, that listening really deeply to what people are saying could teach me something about language and possibility and poetics,” she said. “I think I’m still struggling with how to carry orality on the page, how to work with silence, how to make an energy out of language, and what it means to say something but to be signaling another—how do you track that syntactically or with the ways that marks are made on the page?”

The poem cycle, a closely connected series with varying narrators, that makes up half of the black maria recounts tragic sea crossings made by Black people, focusing most directly on the 2013 sinking of a ship carrying 300 Eritrean migrants across the Mediterranean Sea toward Italy but with echoes of the Middle Passage of chattel slavery.

In one poem, Girmay uses commas to suggest both breath (as in a musical score) and the waves of the sea. In another, she uses periods to compare the losses diaspora demanded in her family and those of the drowned Eritrean migrants:

I mark, obsessively,

the route,

the family-piercing

of the map

in place after place:

[...]

A series of holes

scar the paper with space

nearly flooded by you…

To tell a story with multiple layers is not to intentionally weave complexity; it is to tell complexity in the ways one can, Girmay said. Inviting the reader into such nuance led Girmay to poetic innovations in the black maria, including her use of punctuation and the cast of characters she provides, borrowing from drama. (The reader learns in the cast list that “you,” as in the lines above, refers to those who did not survive the sea crossing.)

“My way of thinking is through poetry,” Girmay said. “I learn to think in the making of a poem.”

The interwoven sea stories in the black maria reveal multiple encounters and relationships with the sea, through personal and historical lenses. “I’m thinking about these histories of sea crossings and how even in my own imaginative practice I did not, for some time, read Eritrean history in relation to African diasporic histories in the Caribbean or North America,” Girmay said. “I’m interested in why I thought to read them separately even though my sound and mind come up through all that sound and mind.”

One can see how poetry in Girmay’s hands shows how ideology can impoverish experience. Looked at this way, it’s clear how Creative Writing, the most popular minor at Stanford, plays a vital role in teaching students to be critical thinkers.

Listening to, reading, and writing poetry can reaffirm our humanity

As a teacher of writing, Girmay closely listens to the stories her students share and reads with them the work of established poets.

She aims “to read deeply in community” and to “learn from each other’s reading strategies,” she said. She hopes to empower students to learn from one another, as they do from the writers whose work they read attentively.

For example, when reading Lucille Clifton, a midcentury Black feminist poet Girmay counts as one of her major influences, Girmay and the students in her fall 2023 African and African American Studies course, Poetry Is Not a Luxury, tried out some of Clifton’s linguistic strategies. Teacher and students made lists of nouns and corresponding verbs and adjectives. The students were asked to use the verbs and adjectives attributed to one noun with another to create effects similar to Clifton’s.

“Everything is kin in Clifton’s work,” Girmay explained. “The streetlights bloom; in another poem, the hair is crying. Something deep about her ethics and orientation comes through in this tendency.”

Girmay shows how a poet’s human experience “can be met by another” and reaffirms her own humanity by listening and responding, on the page and in the classroom.

“Any invitation to slow down and to be in touch with feeling and thinking, in community, seems so basic, but for many of us, such moments are exceedingly rare,” Girmay said. “Our attention is being fought for and bought. Whether or not the poem you make is ever shared, poetry can be a practice in which you are asked to pay attention to what holds your attention, and to sustain a changing engagement with that material.”