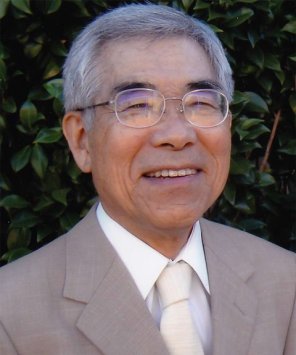

Harumi Befu, professor emeritus of anthropology, dies at 92

Harumi Befu, a pioneer of Japanese studies, helped transform views of Japan.

Harumi Befu, a professor emeritus of anthropology in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences who challenged and exposed stereotypes about Japanese people and their culture, died Aug. 4. He was 92.

A pioneer in his field, Befu was instrumental in establishing Japanese studies at Stanford. He made a profound and enduring impact on his field and on the university community. Students and colleagues remember him as a gifted and selfless mentor, and their pages of remembrances recounting Befu’s contributions, of which only a fraction is represented here, are a testimony to his overwhelmingly positive influence.

Befu’s research revealed how many misperceptions and misunderstandings foreigners have about Japan stem from stereotypes about Japanese people. A bilingual cultural and social anthropologist, Befu published his work in both English and Japanese and wrote, co-authored, and edited 12 books.

In perhaps his best-known book, Hegemony of Homogeneity: An Anthropological Analysis of Nihonjinron (Trans Pacific Press, 2001), he critiqued how Japanese people and their culture were stereotyped and essentialized. The book showcases his versatility as a researcher and comprehensively reviews discussions of Japanese people and culture, called “Nihonjinron,” in literature on ecology, rural community organization, personality, language, values, and ethos.

“He helped transform our view of Japan,” said Raymond McDermott, professor emeritus of education.

“Harumi was a pioneer,” said Gordon H. Chang, the Olive H. Palmer Professor in the Humanities. “He was unique—singular in his scholarship and in his advocacy for a more inclusive and cosmopolitan university. The forward direction of the university after his retirement must have pleased him. He had a large part in making it happen.”

From Japan to The Farm

Befu was born March 20, 1930, in Los Angeles to Juma Befu and Komaki Shimizu. Befu lived in Japan during World War II and returned to the United States in 1947. The experience had a profound effect on him and would later shape his educational and professional careers.

“At the age of 6, I went to Japan with two brothers and stayed there for 11 years, receiving primary and secondary education there,” Befu wrote in a one-page biography. “The spartan education under a totalitarian regime in a starvation war economy certainly left a strong mark on my outlook toward life. (The alternative of staying in the U.S. during the war would have had me in a relocation camp in the middle of nowhere in Colorado. I still don't know which would have been worse.)”

He earned a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from UCLA in 1954, a master’s degree in Far Eastern studies from the University of Michigan in 1956, and a doctorate in anthropology from the University of Wisconsin in 1962. He began teaching at Stanford in 1965.

“He worked furiously, and by the time he arrived at Stanford, he was already an important interpreter of Japanese culture,” McDermott said. “He developed a strong sense that everything in the world happens at least twice—one way in Japan, another way in the U.S., and probably in more ways in other cultures. He spent the next 70 years exploring and explaining the differences.”

Lifelong mentor and friend

“Given my background, studying my root culture was a rather natural thing to do,” Befu wrote in his biography. “I have been back to Japan to research seven times. … I studied the family system, farming villages, inland sea fishing, environmental pollution, gift-giving practices, and many other topics which I hope to share with you.”

Befu did exactly that.

“I think he was driven primarily by delight,” McDermott said. “He took delight in learning and sharing his learning with others. I was lucky to have him as my adviser and later my colleague and friend.”

“I traveled with him a couple of times to Japan—once to give a talk at the National Museum of Ethnology and another time for a conference at Hōsei University in Tokyo," said Amy B. Borovoy, professor of East Asian studies at Princeton University, who earned a doctorate from Stanford in 1995. “Harumi was always gracious and generous—he introduced me to his colleagues and facilitated conversation. … There were few Japanese female scholars attending, and none of the other male scholars had female grad students. But Harumi paid no mind and treated me like a colleague.”

Befu mentored teachers as well. Beginning in 1976, he worked with the Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education to provide local elementary and secondary school teachers with curriculum and professional development to help them teach their students about Japan and Japanese culture.

“He was unwavering in his support of SPICE's Japan-focused project throughout his time at Stanford and truly believed in making Stanford scholarship accessible to younger audiences,” said Gary Mukai, director of SPICE.

Befu served as chair of Stanford’s Department of Anthropology from 1984 to 1987.

He also served in Stanford’s Resident Fellows Program in the 1980s, living with his wife, Kei, and their two children, Marina and Justin, in the dorms to create and direct the educational activities and support the students there. He was the first resident fellow of Stanford’s first Asian American-themed house, Junipero House (now called Okada House), and was later a resident fellow in East House, the East Asian Studies Theme House.

“I knew Harumi and Kei as older parent substitutes who became my friends,” said former student Chad Taniguchi, who lived in Junipero House. “It was the start of a lifelong friendship with Harumi, Kei, Marina, and Justin. Harumi and Kei were steadying influences—mature adults among students finding our ways. Marina and Justin were very young kids, tricycling around the dorm walkways.”

“The Befus encouraged student efforts to educate dorm residents about the World War II internment of Japanese Americans,” Taniguchi said. “Forty years later I learned of their difficult experiences as Japan-educated Americans. … Harumi and Kei made a difference in my life by being caring, concerned, and positive friends who believed in the values of democracy. They are a touchstone to my formative years at Stanford.”

“He provided advice whenever needed but always gave me the freedom to do what I wanted and needed to do,” said David Young, professor emeritus at the University of Alberta, who earned a doctorate at Stanford in 1970. “His dedication and hard work were inspiring to all who knew him.”

Befu retired from Stanford in 1996 but remained active. He was a visiting professor at Humboldt University in Berlin and Oulu University in Finland in 2000 and was director of the Institute for Cultural and Human Research and professor at Kyoto Bunkyo University in Japan from 1996 to 2000.

"Harumi was a pioneering scholar whose work influenced how modern Japanese culture and society are studied around the world,” said Miyako Inoue, associate professor of anthropology at Stanford. “Generations of students and scholars have been influenced by his work. It was my distinct privilege to know him as a person and a colleague."

Befu received numerous honors, including grants from the National Science Foundation (1966-1967 and 1969-1973), Guggenheim Foundation (1971-1972), Fulbright-Hays Program (1978-1979 and 1983-1984), National Endowment for the Humanities (1983-1984), East-West Center (1991-1992), and Japanese Ministry of Education (1998-2000).

“Harumi was a person of integrity. He was not only a highly respected scholar, but also a generous mentor to us all,” said Lisa Yoneyama, professor of East Asian studies at the University of Toronto, who earned a doctorate in 1993 at Stanford. “Harumi had always quietly, but fiercely and stubbornly, rejected any kind of chauvinism, ethnocentrism, and intolerance toward differences.”

“He was happiest when his work articulated with his strong sense of right and wrong,” said McDermott. “We could count on him always showing up and trying to be helpful. He was never mean. I am crushed that I will no longer see his smile or get to play with the probing questions he liked to ask.”

Befu is survived by his wife, Kei; children, Marina and Justin; and four grandchildren. The Befu family held a private family memorial to commemorate Harumi’s life, according to his wishes. In lieu of flowers, contributions in his honor may be made to Amnesty International, Doctors Without Borders, USA for UNHCR, or Planned Parenthood.