Detective stories don’t sell in China. The reason why has to do with Chinese concepts of justice

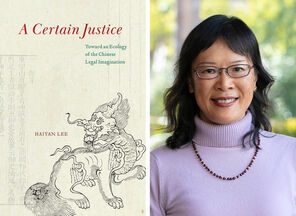

Haiyan Lee’s latest book, A Certain Justice, explores how Chinese and American views of justice, law, and morality shape—and are shaped by—popular culture.

Haiyan Lee, the Walter A. Haas Professor in the Humanities and professor of East Asian languages and cultures and comparative literature in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences, was born and raised in China. As a graduate student in the U.S., she grew fascinated with American concepts of law and justice as revealed in popular novels and movies—what she calls “imaginative literature.” She began to listen to recordings of U.S. Supreme Court cases and discovered ideas of justice that were fundamentally different from those she learned growing up. That journey of discovery led to her latest book, A Certain Justice: Toward an Ecology of the Chinese Legal Imagination (University of Chicago Press, 2023). We asked Lee what these divergent concepts of justice tell us about how the two cultures function.

This Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

Question: What did you hear when you listened to those Supreme Court tapes?

Lee: I just couldn't believe it. There are cases where you have ordinary citizens suing the federal government—not just suing the government, but sometimes winning! It's just something that really boggles my mind. It's unheard of in China. In China, law is something that is wielded by the state to hold the citizens in check, not to protect individuals against the state. It is about preserving the legitimacy of the state. To me, these are completely different conceptions of the term “justice.”

Question: Why did you write about justice through the lens of storytelling?

Lee: As I looked back at the Chinese stories that I’m familiar with, they often dealt with moral conflicts getting addressed outside of legal channels—either politically, informally, or communally. This has led other scholars to view these stories as being about social problems, not legal ones. But the conflicts often involve crimes and investigations, so justice is very much embedded in them. I wanted to apply the analytics of comparative literature to this intersection of law, justice, morality, and popular culture.

Question: Can you explain what you mean by “high justice” and “low justice”?

Lee: I believe these two are the main differences between the Chinese and American concepts of justice. Low justice is familiar to most Americans. It is about fairness and equal treatment of individuals. American law is conceptualized almost exclusively at the low justice level. In China, the state was founded on and derives its very legitimacy from the embodiment of some sort of cosmic justice. This is what I mean by high justice. The overriding goal is the good of the community even if it means some people suffer unfairly. China justified its one-child family planning policy using high justice. The policy meant a great deal of suffering for some, but it was believed good for Chinese society as a whole and was therefore deemed “just.”

Question: You note that detective stories are not popular in China. Why is that?

Lee: While crime and punishment are perennial themes in Chinese literature going back to dynastic times, the classic detective story of the Sherlock Holmes variety was not known in China until the early 20th century. It immediately took off. Chinese writers wrote their own versions of Sherlock Holmes. It was a huge commercial success for about a couple of decades. Then came Mao Zedong, paramount leader of the Chinese Communist Party and founder of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. His regime didn't like detective stories because they entice the reader to sympathize with criminals. As such, they are an implicit critique of the social order. In his regime’s view, capitalist societies are inherently unjust—founded on oppression and exploitation. In an ideal socialist society, there is no oppression and, therefore, no need for detectives or detective stories. The communist regime essentially declared the crime story a bourgeois horror of capitalist society, and these views persist in China today.

Question: And yet the Chinese love spy thrillers?

Lee: Exactly! Spy thrillers are about the state being attacked by hidden enemies. They are about defending the homeland against outside threats. They do not challenge the social order. In A Certain Justice, I compare Chinese spy thrillers and the James Bond franchise and find some interesting similarities and differences between the two cultures.

Question: Who is Judge Bao, and why does he hold such a place in Chinese concepts of justice?

Lee: Judge Bao was a legendary magistrate in the Song dynasty (960-1279) known for standing up against corrupt officials on behalf of commoners. I begin with two Judge Bao stories because Chinese audiences are very familiar with them. A typical Judge Bao story begins with a matter-of-fact description of a crime and some obvious motive. The deed is done, and the scene quickly shifts to Judge Bao. The suspense is not about the reader trying to figure out who did it, but the logic of Judge Bao’s adjudication and the cosmic fairness of the punishment. The drama is not epistemological; it is moral. In fact, Judge Bao is not even a law enforcement officer. He’s an arbiter of the greater moral order—of high justice.

Question: What are you working on next?

Lee: I’m working on a number of small projects. One of these is a paper on the shape of low justice in China’s “Rust Belt,” located in Manchuria. In this paper, I look at how a new urban underclass created by deindustrialization plays cat and mouse with a police force drawn from the same déclassé stratum.