A ‘deep time revolution’ paved the way to American modernity, Stanford historian asserts

In a new book, Caroline Winterer explores how the geologic record upended biblical notions about the Earth’s age for 19th-century Americans, whose reconstructed understanding of time affected their sense of identity and purpose.

Americans’ conception of time underwent a Brontosaurus-size transformation over the course of the 19th century, according to Caroline Winterer, the William Robertson Coe Professor in History and American Studies in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences.

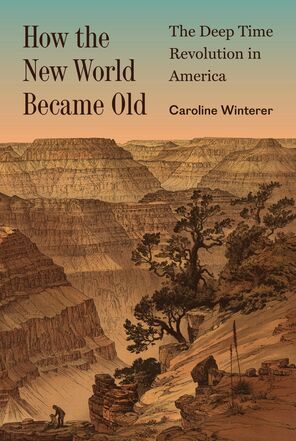

During this period, studies of rock strata and dinosaur fossils upended not only how Americans understood the age of the Earth, but also how they conceived of their homeland and their place in the world, Winterer asserts in How the New World Became Old: The Deep Time Revolution in America (2024; Princeton University Press), published Oct. 8.

Here, Winterer, who is also chair of the Department of History, discusses what she calls the “deep time revolution” and how it shaped American modernity and national identity.

This Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

Question: What was the deep time revolution in America?

Answer: In less than a century, Americans went from believing that Earth was around 6,000 years old—a number they calculated using the dates in the Bible—to thinking it was around 2 billion years old. It was such a massive game changer for Americans that it ranks up there with the political cataclysms we usually call revolutions.

Question: How did this revolution change how Americans understood the notion of time?

Answer: So much about time changed between 1800 and 1900. On the one hand, time got really fast. The Industrial Revolution brought trains and telegraphs, which really jarred people accustomed to riding on horseback and sending letters through the mail. But on the other hand, deep time showed that Earth was billions of years old and that life had evolved very slowly.

It’s no wonder so many people were confused by 1900, the start of the era we call “modern.” Artists and novelists began to experiment with new ways of thinking about time and space. They challenged traditional narratives and perspectives. A lot of modern art emerged from the dizzying encounter with deep time. Rock art in ancient caves inspired artists like Paul Klee to paint in unconventional ways that broke with focused perspective. Some of the first exhibits at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, which opened in 1929, were just photographs of ancient rock art. Some people said that the cavemen had been the first Surrealists.

Question: How did Americans’ perceptions of the continent change as information came to light about its prehistoric past?

Answer: Louis Agassiz, a Harvard naturalist and geologist, wrote a famous essay in The Atlantic in 1863 in which he claims that America was the oldest continent, “the first dry land lifted out of the waters.” Americans began to say that their land was extra special because it was ancient. God must have smiled upon the United States because he had created it first and lavished it with gifts of fossil fuels. Americans created natural cathedrals based on the continent’s antiquity. We know these as the national parks, such as Yellowstone and Yosemite. They are products of the deep time revolution.

Question: How did Americans’ perceptions of who they were change?

Answer: Some White Americans used deep time to argue that they had rights to the continent. In charting its natural history, geologists and other scientists drew attention to the Age of Reptiles and Age of Mammals while relegating American Indians to the role of newcomers—in effect, portraying them as immigrants instead of native-born inhabitants. Paleontologists in the West would say that 50-million-year-old mammals were in fact the first Americans, not the Native peoples currently inhabiting the region. I call this temporal imperialism.

Question: How did America’s relationship with Europe evolve during the deep time revolution?

Answer: For Americans, proving that their country was older than the “Old World” of Europe was essential for securing their place in the international rivalry among nations. Americans used animal and plants fossils to argue that the “New World” was older than Europe.

The United States was a very young nation, unlike its European rivals, such as Great Britain, France, and Spain. Americans were embarrassed about this, as though they were sitting at the children’s table. Plus, their former colonial overlords, the British, had now become scientific rivals in the race to leadership of the Industrial Revolution, which was based on the extraction of coal and other “fossil fuels”—a term coined in the early 19th century.

So Americans had a lot to prove with their fossils. They weren’t just old bones; they were signals to Europe that the United States had won two time contests: The U.S. was simultaneously the youngest and freshest nation politically and the most ancient and admirable nation geologically.

Question: What inspired you to write this book?

Answer: I grew up hiking in the Alps and the Sierra Nevada. Why did I—and so many other people—find these ancient peaks and valleys so awe inspiring? I’ve also loved dinosaurs since I was a kid. The book traces Americans’ love affair with dinosaurs. I made sure to include lots of American dinosaur pictures.

Media Contact

Marijane Leonard, School of Humanities and Sciences: marijane [dot] leonard [at] stanford [dot] edu (marijane[dot]leonard[at]stanford[dot]edu)