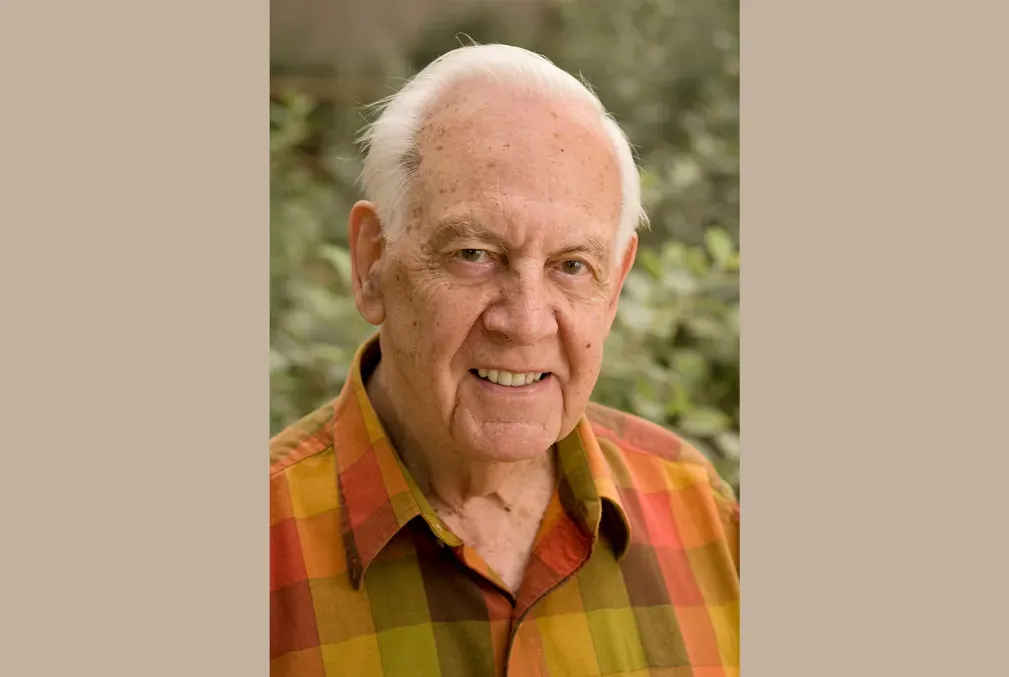

Walter A. Harrison, solid state physicist, has died

Known for his simple explanations of complex concepts, Harrison significantly advanced our understanding of solid state physics, semiconductors, and electronic structure. Many of his books and papers are still widely used today.

Walter A. Harrison, a professor of applied physics, emeritus, in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences, known for his research on solid state physics, the theory of metals, semiconductors, and electronic structure, died March 6. He was 93.

A leading scholar who strove to find the simplest explanations for complex phenomena, Harrison earned a reputation for an honest, no-nonsense approach to solid-state physics. This approach informed his namesake discovery, the Harrison Construction—a simplified way of constructing Fermi surfaces—an abstract interface that describes the state of electrons at zero temperature. In a 2018 memoir, Harrison wrote with characteristic wit that “I realized that you don’t get famous by doing something complicated.”

“Walt was an ideal thesis adviser for me,” said Richard A. Meserve, president emeritus of the Carnegie Institution for Science, who earned his doctorate in applied physics from Stanford.

“At a time when many condensed matter theorists applied extensive computer codes in research, Walt sought to assure real understanding of phenomena by developing simpler models that served to reveal the underlying physics. His approach was not necessarily fashionable, but he was respected by the community for the deep understanding that his work provided.”

Journeys abroad, joyful memories at home

Already an established physicist thanks to his work for General Electric after earning a doctorate from the University of Illinois, he was recruited to Stanford as a professor of applied physics in 1965. He remained a professor for 36 years and continued researching and teaching after his retirement in 2001.

In addition to mentoring doctoral students, he wrote books that remain in high regard thanks to his direct and honest approach. These books include Solid State Theory (Dover, 1980), Electronic Structure and the Properties of Solids: the Physics of the Chemical Bond (Dover, 1989), and Applied Quantum Mechanics (World Scientific Publishing, 2000).

Many of Harrison’s future colleagues first encountered his name through these works, including Hari Manoharan, an associate professor of physics who studied under Harrison and eventually became his colleague at Stanford.

“I am grateful to have known Walt through several formative stages of my own life,” Manoharan said. “I came to Stanford for one year as a graduate student and sought Walt out to take his class on electronic structure. Many years later, I returned to Stanford as a new faculty member and my office was across the hall from Walt in the Geballe Laboratory, where we would debate what should be put in quantum mechanics courses and go to seminars and meals together.”

Harrison earned a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1970 and an Alexander von Humboldt Fellowship in 1982, and his leadership positions include chairing his department from 1989 to 1993. He also traveled extensively for his work in the 1970s, visiting the Soviet Union, China, and East Germany.

Proving his teacher wrong

Harrison was born on April 26, 1930, in Flushing Meadows, New York, to Charles and Gertrude Harrison. Raised in Toledo, Ohio, Harrison developed an interest in physics at a young age, even receiving honorable mention in a talent search for a project in which he argued, essentially, that his teacher was wrong about a fundamental concept regarding momentum. (It turned out Harrison was right.)

He went on to earn his bachelor’s in engineering physics in 1953 from Cornell University, where he also met his college sweetheart, Lucille (Lucky) Carley, whom he married in 1954. Lucky became a docent at Cantor Arts Center and at the Windhover Contemplative Center. Their Eichler home on the Stanford campus became a center for memorable gatherings of colleagues, friends, and family alike.

After retirement, Harrison published his final book on physics, Theoretical Alchemy: Modeling Matter (World Scientific, 2010), and his reflections on his career and life, Practical Alchemy: A Memoir (World Scientific, 2018). The journal Contemporary Physics called his memoir “both a fascinating personal account of his life and work as a physicist, but also an ode to science.”

“I would walk by his house on the way to the local school and stop in to hear his stories or play croquet with his kids,” said Manoharan. “It is from those precious interactions that I truly understood not only what a colorful and impactful professional life Walt had led, but also the depth of love and support he had provided to his wife and children during his lifetime.”

Harrison is preceded in death by his wife, Lucky, who died in 2019. He is survived by his sons, Rick, John, Bill, and Bob; six grandchildren; and three great grandchildren.