Stanford biologists transfer specialized skills to COVID-19 testing

As communities ramp up testing for the novel coronavirus, researchers find opportunities to lend a hand.

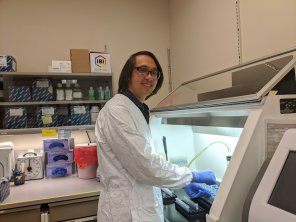

Paul Bump, a doctoral candidate in biology, normally studies marine invertebrates, such as worms, to unlock secrets about biological processes. But as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread across the world, Bump and other Stanford scholars are using their foundational research skills to help tackle the novel coronavirus.

After hearing media reports that the Monterey County Public Health Laboratory faced a staff shortage to meet quickly growing COVID-19 testing demands, Bump realized he could apply his specialized biology skills there. The lab does the majority of testing for Monterey County, California, and neighboring San Benito County—communities south of San Jose. Like many U.S. municipalities, the counties have shelter-in-place orders and face-covering requirements to help prevent the virus’ spread.

The lab typically receives patient samples that come in as swabs and have to be tested to see if there is evidence of the COVID-19 virus. With only three full-time microbiologists, the lab couldn’t hire additional qualified, retired microbiologists because they were all over 60, an age group at high risk of complications.

Bump and other Stanford researchers practice similar molecular lab techniques to those used by the public health lab and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), so they were able to help fill the need.

“It takes skill handling a pipette and working with small volumes of liquid, one microliter,” said Donna Ferguson, director of the Monterey County Public Health Laboratory. This lab can work with dangerous diseases because it has a negative pressure room and biological safety cabinets that allow working with dangerous organisms like the novel coronavirus.

Bump’s regular biological research at Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Station in Monterey County involves RNA extraction and a technique that makes molecular copies—the same process used to determine if there is evidence of novel coronavirus from patients’ swabs.

“Normally, I might discover an interesting biological finding. Now, this affects someone’s life in a meaningful way,” said Bump, who has been spending 20-30 hours each week helping Monterey County Public Health Lab staff test patient samples. “We’re the extra players on the side.”

Since testing began at this lab in early March, at least 2,453 tests have been completed and about 200 positive outcomes discovered. According to the California Department of Public Health, the two counties the lab serves have a total of 237 positive cases and six deaths combined.

The Stanford researchers “just have an amazing amount of energy and dedication,” Ferguson said. “They are here on time. They work as long as we need them to. They do whatever we need them to do.”

Postdoctoral research fellow Brendan Cornwell is among those volunteering at the Monterey lab. Cornwell normally works at the Hopkins Marine Station studying coral bleaching. He has temporarily moved from tackling one global crisis—climate change—to another.

“It’s nice to be able to contribute the sort of specialization I’ve been working on for years, and to apply it to a local set of problems that we’re facing,” Cornwell said.

Cornwell, who is transferring his skills extracting DNA from corals to COVID-19 testing, says going into the lab to volunteer feels like a more normal part of the week, since his Stanford research is currently confined to home.

As states and local municipalities grapple with when to ease stay-at-home measures, a core focus is increasing testing capacities. Diagnostic tests for the coronavirus involve analyzing samples from a person’s respiratory system—which is usually taken via a swab of the inside of the nose. There are also antibody tests that check a patient’s blood sample for evidence of antibodies—proteins that help fight germs—that might show a person had a previous infection.

According to Bump, coronavirus testing is a very detailed process, requiring a whole new level of double- and triple-checking.

“A lot of science is like following a cooking recipe. You have to be cautious about mixing ingredients,” said José Miguel Andrade López, a biology doctoral candidate also helping the Monterey lab’s efforts. With COVID-19 testing, “you are dealing with patient samples and don’t want to misdiagnose anyone,” López explained.

López typically works at the Hopkins Marine Station and studies how vertebrae nervous systems evolved. At the county lab, he has also been helping with data entry and says he didn’t imagine he’d be working in a clinical setting just a few months ago. The researchers must wear personal protective equipment (PPE) to protect themselves and others from transmitting the virus.

López is finding this COVID-19 testing work so gratifying that he is considering making the leap to biomedical research.

“You feel a sense that you’re doing something for the greater good.”